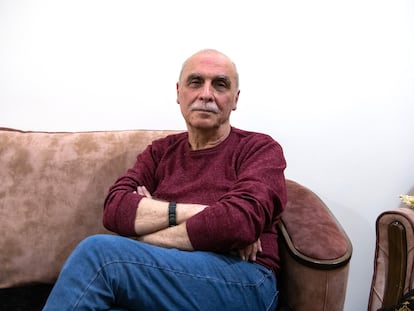

Ahmed al-Sharaa, the former jihadist rehabilitated by Trump who has brought Syria in from the cold

Defined as a shrewd and ambitious man, the leader of the Arab country has combined a firm hand with openness since bringing down the Assad regime

After 9/11 and the ensuing U.S. war on terror, it was unthinkable to see an American president shaking hands with a leader on the State Department’s terrorist list. But current international geopolitics is moving at such a frenetic pace that even this taboo was buried Wednesday: Donald Trump received Ahmed al-Sharaa in Saudi Arabia, until recently known by his nom de guerre, Abu Mohamed al-Julani, a former Al-Qaeda leader, head of the fundamentalist organization Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), and currently the interim president of Syria.

This handshake signified the international rehabilitation of the former combatant, behind which there has been significant diplomacy from regional powers (Saudi Arabia and Turkey, in particular) but also the political intelligence of Al-Sharaa, a man accustomed to walking on the edge of the precipice and who, in the barely five months since he led the offensive to overthrow Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad, has achieved the important milestone of freeing his country from international ostracism. Furthermore, with Trump’s announcement that he is lifting U.S. sanctions against Syria, Al-Sharaa has scored a point celebrated by a population that continues to live in the misery of a country devastated by more than 13 years of civil war (although experts warn that the effective withdrawal of these sanctions will take time, as it involves a tangle of laws, orders, and regulations, not all of which depend on the U.S. executive branch).

“Young, attractive guy. Tough guy. Strong past. Very strong past. Fighter. He’s got a real shot at pulling it together. It’s a torn-up country,” Trump told reporters after his meeting with Al-Sharaa. Those who know the HTS leader and have followed his transformation from jihadist to statesman — a change that has also been reflected in his image — describe him as a shrewd, charismatic, and ambitious individual.

He was born into an upper-middle-class family expelled from the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights. His father was an academic who worked as a government advisor to the Assads (Bashar and his father, Hafez), and his brother Hazem was a Pepsi executive in Iraq. But unlike the pan-Arab nationalism his father espoused, the young Al-Sharaa was drawn to Islamism in the heat of the Second Palestinian Intifada and 9/11. In 2003, at the age of 20, he went to Iraq to fight against the U.S. occupation, but spent most of his time detained in Iraqi prisons or under U.S. control, where he strengthened his ties with Al-Qaeda fighters and future leaders. Back in Syria, in the midst of the civil war, he played on the differences between Al-Qaeda and its offshoot, the Islamic State or ISIS, only to end up leaving both in the lurch (experts believe that without the intelligence information provided by his group, it would have been impossible for the U.S. and Turkey to execute jihadist leaders hiding in Idlib, HTS’s stronghold in Syria).

Obsessed with the spotlight

Some of his former comrades in arms don’t hold him in high regard: they consider him a figure obsessed with the limelight, willing to “sacrifice the blood of his soldiers.” But perhaps it is this ambition and desire to go down in history that have led him to adopt a pragmatism unthinkable among other jihadist leaders.

During his months in office, he has combined a firm hand with openness. A human rights activist criticizes the “undemocratic” process and the “hasty” manner in which Syria’s transitional Constitution was drafted, a text that concentrates power in the president, with hardly any oversight mechanisms. Although he has appointed members of different faiths and ethnicities to his Cabinet — and even three ministers who served under Assad — and has not imposed any more religious legislation than the one in place until now, he has only given one ministerial portfolio to a woman and has reserved the most important ones for his closest circle of collaborators (all Islamists). Furthermore, as Human Rights Watch reported on Wednesday, he has appointed rebel commanders accused of war crimes to important positions in the new Syrian Armed Forces.

Al-Sharaa is performing a balancing act, seeking to appease both his fundamentalist comrades in arms — who claim the fruits of victory for themselves — and the majority of the population, who are suspicious of them. After more than a decade of civil war, Syria is not only a devastated and impoverished country, but sectarian tensions have also worsened. Some representatives of ethnic and religious minorities demand the federalization of Syria and seek the protection of foreign powers for their groups, while Al-Sharaa is committed to maintaining centralized power to avoid failures similar to the Lebanese, Iraqi, or Bosnian models.

Of course, these past five months have not been easy. While the new government sought to change the composition of a state dominated for half a century by the Assad family and their cronies and keep the administration functioning, there has been virtually no respite from Israeli bombing of the country, including in the vicinity of the presidential palace (Al-Sharaa has openly stated that Syria will not respond because it would be suicidal for the country and, instead, has established negotiating channels with Israel). It has also faced a major uprising promoted by members loyal to the former regime — whose brutal repression was widely criticized internationally, and resulted in the deaths of hundreds of civilians — and conflicts with various groups of the Druze minority — some of them actively supported by the Israeli government of Benjamin Netanyahu — despite which it has reached agreements with some of the main Druze leaders, defusing a potentially explosive situation. Likewise, he has reached an agreement with the leader of the Syrian Kurdish militias for the gradual reintegration of the territories it holds, the northeastern third of the country, under Damascus’ control.

All this happened at the same time that the new government was leading a diplomatic offensive to normalize Syria’s position on the international stage, hosting representatives from dozens of countries — including Russia and the U.S. — and international organizations such as the UN and the EU in Damascus. Its foreign minister, Assad al-Shaibani, participated in the Davos Forum this year, and Al-Shaibani himself, in addition to traveling to several neighboring countries, was received at the Élysée Palace by Emmanuel Macron last week. However, not everything is a bed of roses: the Syrian president has had to cancel his participation in this weekend’s Arab League summit in Iraq following protests from local Shia groups, who accuse him of crimes committed during his time as a jihadist in the Iraqi branch of Al-Qaeda.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition

Tu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo

¿Quieres añadir otro usuario a tu suscripción?

Si continúas leyendo en este dispositivo, no se podrá leer en el otro.

FlechaTu suscripción se está usando en otro dispositivo y solo puedes acceder a EL PAÍS desde un dispositivo a la vez.

Si quieres compartir tu cuenta, cambia tu suscripción a la modalidad Premium, así podrás añadir otro usuario. Cada uno accederá con su propia cuenta de email, lo que os permitirá personalizar vuestra experiencia en EL PAÍS.

¿Tienes una suscripción de empresa? Accede aquí para contratar más cuentas.

En el caso de no saber quién está usando tu cuenta, te recomendamos cambiar tu contraseña aquí.

Si decides continuar compartiendo tu cuenta, este mensaje se mostrará en tu dispositivo y en el de la otra persona que está usando tu cuenta de forma indefinida, afectando a tu experiencia de lectura. Puedes consultar aquí los términos y condiciones de la suscripción digital.